Kite:

When you are approaching composition, especially with pieces that involve land formations, do you feel that there is a loop where you understand composition is based on the land and the land is contributing to your composition, or is the composition a gift to the land? Do you see that your tools are in flux? I’m thinking about some of the instruments in Death Convention Singers.

Raven Chacon:

Yeah, that’s a good question. There’s a lot of reasons I do things outside and it might be the kind of surface response to the history of the place, for instance, or they have history of the abandoned building or something. That’s one reason for doing it. And then obviously playing outdoors, there is going to be that response, those other elements, those other sounds, birds, planes, airplanes in the sky, the wind. The very acoustics of where it’s at, like if it’s rocks, it’s in a canyon. That, of course, is another thing to respond to.

I like to think that maybe the sound is getting trapped inside this place, that there’s some other kind of time happening when playing outdoors. And one is just merely a participant in that. It’s already going, it’s ongoing, not in a John Cage kind of thing either, but maybe you’re inserting yourself if you go take your cello out to the desert, that maybe trying to place the emphasis or the priority, or even like this discussion of the point of view isn’t coming from you, it’s not even for you to respond. You’re just a part of it, and listening is going to be a big part of that.

I don’t know if it’s a call and response thing or you’re jamming with the birds or anything funny like that. It’s more trying to make things line up with other things without it being a response. That’s been an interest of mine for a long time. It’s just trying to maybe read the cues.

Maybe there’s a rock I’m sitting with outside, and maybe there’s some kind of correspondence or some kind of cue, or some higher knowledge or connector is giving me information that I maybe can respond to. And if you have an instrument, maybe that’s something that can react to it, I suppose. I don’t know if that describes it, but I think it is something very different than just saying I’m going to go out in the desert and play with whatever I hear, listen. It’s not really like a deep listening thing like that either, but it’s definitely a recognition of the place. It’s definitely a recognition of yourself in the place, but without being a major player in that place.

Kite:

I think that’s kind of how I was reading it. I was thinking about your recent scores that are symbol heavy and how they’re in dialogue with different Indigenous semiotic forms and different ways that symbols translate from and the environment, environmental cues of millennia, of finding ways to express that visually. And then coming out in 2021 with a sound or a group of people making sound. I mean I’m wondering about how you choose your symbols.

Raven Chacon:

With those Zitkála-Šá series, it’s almost like portraiture, like considering the person’s work both visually and sonically. Also, whatever else I know about them might end up somehow in the score. And this could incorporate things like numbers or other music notation, other traditions, but also can incorporate Indigenous symbology, geometries, other things that may or may not be relevant. With that series, I didn’t necessarily go tribal-specific into anybody’s tribal traditional artwork or anything, but it was more just kind of somewhere in between all of that.

My hope is that it is in line with some kind of, I don’t know, I always have a hard time saying contemporary Indigenous aesthetics or anything, but I mean that’s what we do. I think it’s inherent in what we all do, all of us who do this kind of thing, maybe, and because we still prioritize other things. I mean, obviously, these are music scores or some other kind of score.

American Ledger no. 1, Raven Chacon (2018)

Kite:

I guess I’ve seen the one on Soundings?

Raven Chacon:

Yeah. The American flag one. Yeah, yeah. That one kind of plays with musical notation, standard notation, and then there’s other kinds of shapes like crosses. In the beginning you see a cross and then later it’s inverted into the Christian cross, but initially that cross could be a star and then later you see a five-pointed star. So you kind of see, the way that that image like a star has been subverted through colonization. What’s another one in there? Waves, they’re very simple in some ways, but it’s still kind of expressive and dynamic and they kind of float between having specific meaning and not, they’re sometimes a bunch of dots, that’s going to be a pointillistic sound, but it’s going to have an instrument assigned to it.

I mean the other thing I’ve been getting into too is like texts. Are you aware of the score Candice and I made about Standing Rock?

Kite:

Yeah. I haven’t looked at it.

Dispatch, Candice Hopkins and Raven Chacon (2020)

Raven Chacon:

So that one is about trying to be a transcription of what unfolded, what I saw unfold at Standing Rock. But ultimately saying, there was maybe not listening, not enough listening happening to what the land wanted and maybe trying to understand cues from the land and seeing how we can relay those cues in some kind of organization, some kind of direct action organization. Because we had every walk of person, walk of life at Standing Rock. You had Burning Man people, you had urban natives, you had traditional natives, you had journalists, we had fucking cops.

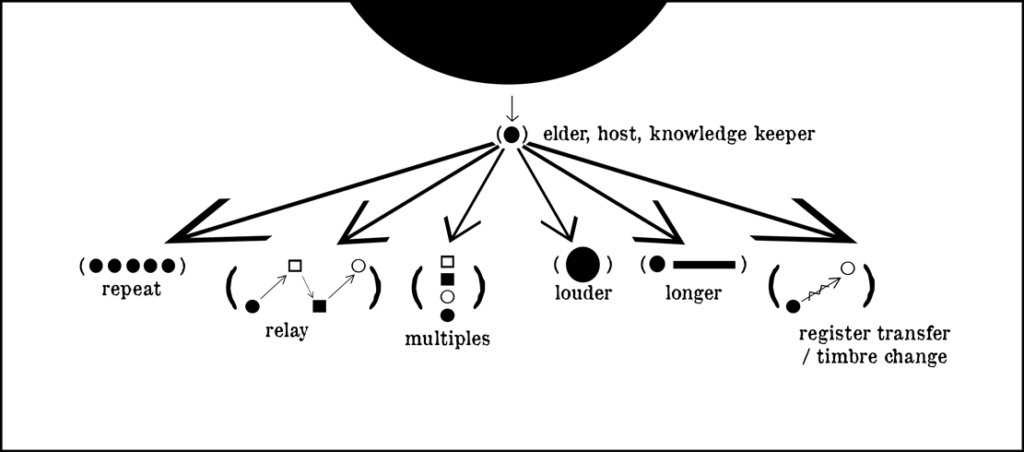

And so just trying de-noise all of that, I suppose. That’s kind of how we’ve been describing that score. But ultimately saying there’s a source that is, we’re trying to relay a message from, and that would be the river or a rock or a tree that’s going to be cut down. I don’t want to call it an ecological score. It’s more kind of trying to decipher dynamics or filter dynamics and then be a score for relaying information.

Whether that information is one-to-one, you’re at the next encampment and I’m trying to share something with you or vice versa. You’re telling me something or it’s like social media, like you are somewhere on the front lines of some place and you’re trying to share with everybody, what the fuck is going on. That kind of thing. And it’s very loose, it’s both a prescription and a transcription, but what’s the possibilities of reenacting this scenario.

When you have more time, you should perform it. We’d love to see a performance of it.

Kite:

It’s basically like that game where everyone plays these different characters, Werewolf.

Raven Chacon:

Yeah. Yeah. That’s how we’ve been describing this, kind of like part role-playing game, part transcription. And I know I’ve been describing it as a critique of deep listening where there is that privilege of going out in the woods and listening, but also what’s the deepest, when there’s DAPL security with hoses spraying at you or drones or whatever, cops turning LRADS onto you or bullhorns. So it’s part of that too, saying that there is a responsibility if you’re going to be defending the land, I suppose to … And you’re wanting to listen or use the information of what’s around you to also include that into the deep listening of the land. It’s not all just going out in the woods and meditating.

Kite:

What do you think of deep listening?

Raven Chacon:

I like to think that they were coming from a place of wanting to learn about the land. But I think my only critique and the way I’ve been talking about it in relation to this score is saying that there is an opportunity to choose. I think that’s even in the deep listening website.

Deep listening as developed by Oliveros, explores the difference between the involuntary nature of hearing and the voluntary selective nature of listening. I wonder about the involuntary selective nature of listening or that privilege of having to be able to select listening. I mean that’s kind of a hierarchy in itself, right, of saying, I get to choose what I want to hear.

I mean we as humans, right, that’s how we work, but it’s saying, well, what if it’s discounting a creator, I think. It’s discounting what you’re talking about of the agency of objects to have a voice, that there’s other power out there. And I like to think that there’s involuntary non-selective listening that’s also happening. And she’s saying between hearing and listening, yeah. But I think it goes, it’s in conflict with two things, it’s in conflict with real views that we might have about objects or nonhuman voices. And also it goes back to this privilege of saying, well, shit. I mean I can’t volunteer to hear that the LRAD from the cops beaming at me or people screaming at me, telling me to get off the camp or whatever, so that kind of thing I think is weird.

And it goes back to just assuming that one can just go into these places and listen, and gain the information without knowing any context, no history, not knowing what the stories are of that place, the songs that have been sung in that place, all of that. So that’s my question with that stuff. But again, my only knowledge of deep listening is the people who’ve claimed deep listening as their practice. There’s the deep listening certification or whatever. So whenever I hear that I’m like okay, well …

Kite:

That would be really funny, an “Indigenous listening certification course”.

Raven Chacon:

There you go. Another thing about that, I’ve never asked anybody this, but every now and then you meet one of these deep listening folks. And what does that mean? Does that mean they have knowledge about a place, because this is very site-specific when they say they’re deep listening certified. My next question would be like, where did you go to listen? And then they would say, oh, I went out to Sedona or something. And then I’d say, well, tell me about Sedona then? What did you hear? It’s starting to say they have knowledge about a place. And I’m wondering why I should ask them about the knowledge of a place. And maybe it’s a critique of myself. Why do I know the deep listening person and I don’t know any Indigenous people from that area too?

Kite:

Maybe apart from deep listening is if we’re more listening to a place, or in a place, or at a place, are we gaining knowledge? Is that the end goal? Is that what a Lakota listening form or Navajo listening form is? Is it a technique to gain knowledge? Which I’m not sure it is.

Raven Chacon:

Yeah, you’re right. I mean I shouldn’t assume that’s all it is, but that’s my skepticism is that, that’s what they’re saying when they say that they have a deep listening. Surely, maybe there’s some kind of alignment they’re trying to have with a place, which is very valid. And I would say everybody could potentially have that right without getting into issues of trespassing and this or that. If somebody just found themselves in Sedona for whatever reason. Sure, you might try to align with that. But then it gets into that like we’re saying this, well, wouldn’t part of that alignment be more research or understanding or knowledge about the tree that is right there, or this canyon or this water, and then other steps to that too.

I mean I don’t want to shame anybody and saying, well, they’re just going and taking from the land, but maybe there’s other actions too. So if deep listening involves tourism, going to different places and doing deep listening, or it involves embedding yourself, or doing actions around your home. Getting involved ecologically with what’s happening, protecting waterways, all of that, those are two different things. Those are two different actions.

Kite:

Yeah. I feel like this critique could also be extended to the phrase “listening to the land”, any engagements with ideas of the land, but actually, no, sometimes we are truly not listening to the land, sometimes we’re in a gallery, sometimes we’re on Zoom.

Raven Chacon:

Through a video. Yeah. You’re going to listen to the land through a sound piece or something.

Kite:

Yeah. And it makes me think, well, is that really the methodology that we’ve been taught? Is that the end goal? It confuses me. And I think that’s where I see maybe a tendency towards using and abusing sound art or people doing sound art sometimes. There’s a shallow engagement with sound and listening in the art spaces.

Raven Chacon:

Yeah. I mean I think to respond to what you’re saying, it could become a larger critique of something like field recording for instance, what are we still doing with this? What are we connecting to? It reminds me that there’s other kinds of embedded information, let’s say in a song. Learning a song doesn’t have to be like that kind of listening where we’re just listening and taking in, but it’s actually understanding what the elements of a song might be about, where it was composed, who could sing it. All of that contains information about people, for one.

And then it’s going to also by extension be talking about land and other things. What are the carriers of the song even talking about this? The modes of talking about it? I feel like there’s certain things that don’t always have to be secret. Surely, there’s ceremonial songs we wouldn’t share with others, but maybe there’s other things we could…There’s other kinds of ways of sharing musical traditions. Like how animals communicate, our knowledge of that. That might be very land specific. It might be very tribal specific.

I don’t think field recording is going to cut it. Another thing I’ve been concerned about when I teach these kids on the Rez, there’s always this urge to talk about tribal music, our own tribal music and share that with ourselves. But then because we’re composing, we’re not trying to subvert that song or anything, we want to make new art, but at the same time, maybe there can be some influence in there, but maybe the power of whatever that influence is not going to end up in the composition.

Kite:

Yeah. That wouldn’t necessarily be appropriate.

Raven Chacon:

It might not be appropriate. You have to make a composition that could maybe do the same thing or it kind of is discouraging. It’s like, well, why make something new when this perfect song already exists? So maybe could we compose new songs that talk about this canyon. And how do we do that? I don’t know if it’s like analyzing the pitch of this song or rhythm. It’s none of that. It’s some other embedded information that might have that in the next version or the next carrier of that information.

Kite:

Well, what kind of things are your students inspired by that they start from?

Raven Chacon:

Well, whenever I first have one of those students, we don’t have much time, we have a week. And some of them, as you know, are very shy native kids. And so I just want to understand what they know about as far as music notation, because that’s going to be the language they have to speak with the quartet. But I mean, like any teenager they’re into heavy metal, hip hop, all that stuff, reggae sometimes. And so I just try to throw all that in there, but I try to find if I can hear like Hopi music or Navajo music or wherever I’m teaching in there and try to kind of bring that out as well. Sometimes a kid has some interesting narrative or conceptual ideas too. And I encourage those as well.

Kite:

Thanks, Raven.

Raven Chacon is a composer, performer, and installation artist from Fort Defiance, Navajo Nation. As a solo artist, collaborator, or a member of the artist-group Postcommodity, Chacon has exhibited or performed in the Whitney Biennial, documenta 14, REDCAT, Musée d’art Contemporain de Montréal, San Francisco Electronic Music Festival, Chaco Canyon, Ende Tymes Festival, 18th Biennale of Sydney, and The Kennedy Center. Every year he teaches 20 students to write string quartets for the Native American Composer Apprenticeship Project (NACAP). He is the recipient of the United States Artists fellowship in Music, The Creative Capital award in Visual Arts, The Native Arts and Cultures Foundation artist fellowship, and the American Academy’s Berlin Prize for Music Composition.