I am watching people listen.

At first, they do it quickly, in passing, moving though the hallway of MoMA on their way to the Soundings show. Tristan Perich’s piece, Microtonal Wall, is installed in this hallway. It is flush with the wall, projecting sound outward, into the passageway. If it were a painting it would be easy to manage: you’d step back a few feet, looking over your shoulder to make sure you’re not backing into someone else, and then turn to face the art, to look at it. You might move forward a little after contemplating it in all is gestalt-glory, then lean in to examine a detail on the canvas, wondering how it was made, and then step back again. You can’t get too close because it is too precious an object for the body to touch or even breathe on. And because you’d get in trouble with the guards.

Perich’s piece poses a problem. The museum visitors are not sure what to do about the fact that their ears are not in the same place as their eyes. Walking by the piece, they pause for a moment. They backtrack and turn to face the wall of speakers. But this doesn’t really work, because the eyes don’t hear. So then they slide up to it sideways, getting their ears as close as they can to the tiny speakers, almost like a cat rubbing against a piece of furniture. As each of the quiet, tiny speakers is playing a slightly different sound, the listeners writhe along the wall, stooping down low to catch the pitches coming from the bottom near their calves, then straining upwards on their tip-toes to hear the sounds from above their heads.

Almost everyone is irreverently ignoring the line of black tape on the floor in front of the piece, meant to mark off the area across which you cannot step in order to protect the piece from being touched. Ears rub against the piece, people lean in towards wall and barely balance, strands of hair get caught by the static electricity generated by the fuzzy fabric membranes of each little speaker, and stay on the piece long after their owners have left. At this point on a busy Saturday afternoon, five people are leaning up against the piece, while a handful more cluster around them, waiting for their turn. A guard walks by, looks at the listeners, and throws his hands in the air. He shakes his head and keeps walking.

Listeners in front of Tristan Perich’s Microtonal Wall. Photo: Jessica Feldman, 2013

I am starting this article with Perich’s piece because I think its reception simultaneously articulates the strength and the problem of sound-as-art. This work, and sound in general, activates, problematizes, and obviates the black line on the floor. Microtonal Wall probably wasn’t conceived to address the breaking of institutional boundaries, but by virtue of the phenomenological operations of sound and its placement in a museum setting, it starts to ask questions it might never have meant to ask. Questions about language, politics, money, and ethics. I will address these questions in this article and attempt to explain why I think they were mishandled by the show. My main argument is that sound is an inherently, and especially, unwieldy medium for the gallery space, both technically and ideologically. Because it radiates out through space, and draws in bodies, it’s hard to hold in a cordoned-off commodity-form. Furthermore, and even more exciting, it is very often a transmitter of language, ideas, and feelings. It puts people in relation to each other’s thoughts by vibrating their bodies. One would hope a show of soundings would be largely about connections and conversations.

Perich’s piece is about resolution, in the digital sense of the term. The piece consists of 1500 tiny speakers, each of which is connected to its own simple microchip, which generates rapid electrical pulses that we humans hear as pitches when sent through a speaker. Each circuit pulses at a slightly different speed, generating microtonal variations in the pitches that are heard from adjacent speakers. By drawing the ear close to the wall (zooming in, if you will) the listener is able to hear these discreet tones. In the middle ground we hear dense discordant harmonies, and white noise when we stand farther back. The piece demonstrates to us the thresholds at which our listening apparatus slides from understanding a signal to apprehending noise, and points to the fact that these classifications are subjective, personal, and embodied. As with much work in the minimalist tradition, the listener turns back on herself to appreciate the piece: the work is felt by delighting in and analyzing its phenomenological and somatic operations in the body and brain. You can spend a lot of time reveling in these operations.1

This is fascinating, and a great lesson is psychoacoustics. But, to me, the best part of the whole thing was what happened around the tape on the floor. This line of tape is the only symbolic gesture in the piece – and, admittedly, it’s not part of the piece, but part of the museum institution. The black line is language: is has a clear meaning, it has a specific history, it has a politics and power implicit in its inscription on the floor. We know what it’s trying to say to us and have to decide whether to listen and how to respond.

The piece – and the show, and sound art in a gallery – poses a problem for the gallery institution, not just for the listeners. The fact that our ears don’t work like our eyes becomes a political-economic issue. That issue is a fertile, powerful one worth addressing through sound. In fact, it might be one that can be addressed particularly well though sound, as it is a medium that carries through walls, moves bodies, and is not easily fixed in a plastic, solid, saleable form. Instead however of embracing this latent social power characteristic of sound, a lot of the work in the MoMA show was happy to stop with a demonstration of the medium’s acoustic and bodily operations. As such, the show missed a vital opportunity to connect the magic of the phenomenology of sound with the problem of the politics and economics of listening and sounding.

Sound art reiterates a problem that the museum institution has been turning over for decades now: What if a work of art is made of something that can’t be owned? What if it is made of something that is about movement and relationships? What does that say about what the art is there to do? What does it say about the physical and economic context in which this art can do what it does? Can sound do its thing in a gallery? Can a gallery hold art that isn’t an object? Can the art institution provide for work that doesn’t care whether it makes for good currency?2 I think the MoMA show struggled with these questions, and I think that the longing towards commodities is part of the reason that the show leaned so heavily on the physicality of sound. Sound-as-object got privileged over sound-as-language, stopping short of the very politics and relationality opened up by such physicality.

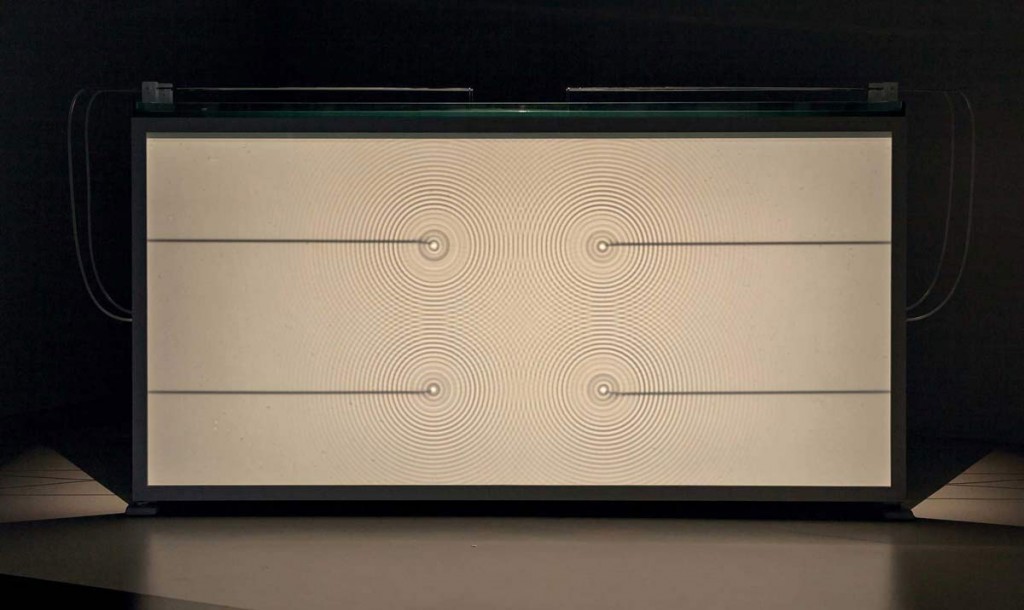

Perich’s piece is an example of this. Carsten Nicholai’s kinetic sculpture, Wellenwanne Ifo, used water, mirrors, and light to give visible and plastic form to subharmonic sound waves3, creating an almost psychedelic, strobing, radiating object, which visually stimulated the viewer. The piece embodies inaudible vibrations and transmits them through other media to affect the viewer’s neurology. Similarly, if more personably, Luke Fowler & Toshiya Tsunoda’s Ridges on the Horizontal Plane used sound for its physical operations: a fan blowing towards a projection screen caused the screen to touch off a taut piano string, which then resonated through the room, vibrating the air further, and disrupting the projected visuals. According to the wall text, the work explored the “mechanics of perception.”4 This description is accurate, if reductive. The piece used the vibrating string and delicate screens to draw a metaphorical line from the operations of sound to those of vision, reminding us that fluctuations in air pressure affect the skins of the eye as well as the membranes in the ear. The piece opened up the delicate dynamics of perception to reveal a more holistic model of the sensing body.

Carsten Nicolai, Wellenwanne lfo (2012). Water tank, water, mirror, audio equipment, stroboscope, display screen. Photo: Osamu Nakamura

Christine Sun Kim’s and Sergei Tcherepnin’s works also deal with the body, but in ways that move closer to thinking about how sound can get us out of our own heads and in relation to others. Tcherepnin converted a used wooden subway bench into a speaker by mounting transducers underneath the seats. Listeners could experience the sounds with their whole body, by sitting on the humming, resonating bench and feeling their bodies move in sympathetic vibration. It is a simultaneously pleasurable and awkward experience to sit in a foyer MoMA, next to a total stranger, and have your ass vibrated. The piece was more than an edgy massage chair, however. The sounds were composed and the spatialization of the sound through the body was deliberate and crafted. The work drives home the point that objects, like the body and the bench, resonate with and are activated by sound. The dividers in the subway bench, which are designed to partition off private spaces for the sitters and to keep homeless people from sleeping on the bench, also vibrated. In a way, they failed to do their socially assigned job just like the tape failed to keep listeners from rubbing up against Perich’s piece. Tcherepnin’s work takes responsibility for this quality of sound. The piece is about the way that sound breaks down the barriers between mediums, between objects and bodies, between one body and another. It facilitated a kind of physical intimacy between people and things, evoking the possibility of queering hearing: of perceiving sound and feeling intimacies in non-normative spots and sites, subverting public structures for private pleasure. It would be easy to move from this physical experience to a more social or political proposition about the vibratory, pervasive nature of being and the necessity of feeling each other as related “bodies without organs.”5 I’m not sure the piece fully took me here, however, because it wasn’t facilitating expression or communication for the listeners, only sympathy of feeling.

Sun Kim’s drawings deliberately foreclose vibration. The works capitalize on her hearing disability and depict her inner life in visual form. As a Deaf person, Sun Kim experiences sounds based on the way they vibrate and inhabit parts of her body other than her ears. Her drawings use a range of languages to articulate her experiences and imaginations of sound, or its lack. All. Day. displays a large black arch, which traces the sign language gesture for “all day,” coupled with the musical sign for a long rest, which signals to musicians that they must be silent for a specified duration. She touches on the gnostic qualities of language – symbols that hold secret meaning for the initiated groups, juxtaposing the Deaf and classical musicians.

From a disability studies perspective, I was torn about this work. It appears scrawled and raw, and clearly was made in real-time through the performance of the brief gesture. While this testifies to the fleeting and visceral nature of motion, I think it does a disservice to Sun Kim’s capacity for creating more wrought or crafted work using and about sound, which constitutes a large part of her activity as a composer and sound artist. However, in their sparseness, her drawings accomplish something. The viewer is asked to imagine Sun Kim’s experience of sound and silence, and to recreate this experience in their ear’s and mind’s eye. At first, I resented this. I felt deliberately “left out” of the artist’s experience of all-day silence, and felt she should have tried harder to share this in the piece. The valences of disability flipped as I became aware that I was the one lacking in the capacity to perceive this sound-world as Sun-Kim does. The piece felt like it sat on the cusp of hostility and empathy. By presenting a visual depiction of a (lack of) sounding I could never know, the piece made a point of excluding me. It stubbornly situated itself across two mutually-exclusive languages, and refused to provide a visceral translation for the illiterate viewers. This generated in me a deep sense of ignorance and frustration, and an awareness of the inescapable differences between experiences and between bodies. Communicating these feelings of incommensurability and exclusion is no small feat. Sun Kim’s work gets us try to imagine the experience of someone other than ourselves. She owns her authorship, even if it is by shutting us out.

Christine Sun Kim. All. Day. 2012. Score, ink, pastel, and charcoal on paper (left). Discarded earplugs below drawing (right). Photos: Jessica Feldman, 2013

Susan Philipsz’s work is one of the other pieces in the show that thinks about process and authorial intent in sounding. She does this by deploying absence. For Study for Strings, Philipsz made a multi-channel recording of only the viola and cello parts of an orchestral work of the same name, composed by Pavel Haas in 1943 while he was a prisoner in the Theresienstadt concentration camp. Haas, along with most of the prisoners’ orchestra, was executed shortly after its completion.

In Philipsz’s work, each note is isolated and sent to a single speaker, so that harmonies are only possible when the speakers are positioned in audible proximity to each other. The piece was originally installed in 2012 as a public, outdoor installation at dOCUMENTA (13) in Kassel, Germany. The speakers were placed alongside and in between the train tracks at the Kassel Hauptbahnhof, the station from which prisoners were deported to Theresienstadt seventy years earlier. Listeners stood at the far end of a train platform, while individual pitches of the fragmented piece rose up around them, some from very close by, some from far off in the distance, barely audible.6 The absence of the other instrumental voices and the distribution of the viola and cello drive home the feeling of loss and fracture to which the piece is a testament. The piece juxtaposes the collaborative, live nature of performed music with recording technology to ask us to think hard about who is and isn’t present, which voices survive, and what it means to make a memorial.

In the MoMA installation, eight raw speakers were mounted along a wall in a single, small room, encouraging us to take the sound as a whole. As a whole, it still sounds pretty broken: the counterpoint is lacking, we’re not sure what the affect or narrative of each section is, the timing of the voices feels askew. The lack of the other players degrades the composition, and yet this lack isn’t really articulated in the gallery installation as it was at the Kassel site. More importantly, we are hearing a recording of a long-form, through-composed, linear work, and we are given a place to sit and listen to it as such. A careful museum-goer, who has read the placard before entering the room, understands to listen for absence and to imagine the loss of the other voices when experiencing the piece. More likely, the visitor comes in at some point in the loop, listens for a few minutes, and leaves. Whatever relationships could have arisen in the listener’s imagination of the original composer and players get erased and conceptualized. We think about loss, but we don’t really feel it in this installation. This piece was a great relief to me as I wound my way through the show. Finally, I thought, here is a work about people. Here is a work that takes on a painful topic that needs to be sounded. I am very critical of the ways in which the move to the gallery space changed this piece, but this criticism flows at least in part from my interest in the work and its subjects.

The clever move in the Kassel installation was to splay out the instrumental voices across the tracks, forcing listeners to engage with the site and to grapple with the fleeting nature of sound (and human life) as their listening through the space attempted (and failed) to bring together these recorded pitches in the same time and place. The MoMA installation negates this move: the speakers are brought close together and the sound starts to congeal. In this case, we literally can observe the ways in which the move into a gallery space can cause a piece to begin to glob into an object. The power of this work was in its dispersion, and the imagination that dispersion required of the listeners because of the empty holes it articulated: in time, space, ensembles, and communities.

Susan Philipsz, Study for Strings (2012). 8-channel Sound Installation. Photo: Eoghan McTigue

The project of imagining others and their loss bring us in proximity to the work of Emmanuel Levinas. Levinas was a Lithuanian-French-Jewish philosopher, who spent a good part of World War II in a Jewish Prisoner-of-War camp. After the war, he developed a theory of ethics that hinges ethical relations on co-presence, using the metaphor of live, face-to-face interactions. In this kind of encounter, says Levinas, it is impossible to reduce the other to an abstraction or to sameness with the self. In fact, ethicality requires the recognition of difference and the construction of the self in relation to the other. One cannot know oneself without a contrasting other, and one cannot exist ethically or operate politically without first recognizing that there are others out there in the world whose experiences are fundamentally different from those of the subject.

I am interested in Levinas’s idea of ethics as a way out of the sameness and phenomenological obsessions of sound art. As an exercise, consider a binary: juxtapose ethics with sympathy. Sympathy derives from Latin and Greek words meaning “having a fellow feeling.” If we feel sympathy for someone, we claim to feel her pain. If we act to help this pain, we don’t act ethically, we act somewhat selfishly, because we are feeling it ourselves. “Sympathetic vibration” is a technical term in acoustics for the phenomenon that occurs when a when a body resonates because it is exposed to sound vibrations, and therefore is moved to vibrate itself at the same pitch (or at a strong partial.) A great deal of the work in the MoMA show demonstrates sympathetic vibrations – inside the listeners’ bodies, in the objects around the sound source, in the air or water nearby, etc.

This aesthetic assumes that we most convincingly attend to a piece through the sensory experience of the medium in the viewer’s/listener’s body, not from the hard and humble work of trying to understand and respond to the demands of another perspective. There is a thesis about humanity here: that the way we know another (person or thing) has to be fundamentally hinged on the feelings, security, and preservation of the self. The underlying idea here is sort of close to capitalism: people act as self-interested individuals, and what wins out in the end will be what benefits for the most (powerful or effective) people.

This positioning would require that something that gets inside the listening subject, as sound does, has to steer clear of anyone else’s perspective and needs. Sound, at once a vibrating gesture and a carrier of language, wants to break down the sympathy/ethics binary, even if the market would rather it didn’t. This is the deeper – perhaps even unconscious – reason for the dominant aesthetic in the MoMA show. The anxiety about how to handle sound in the architectural and economic context of commodity (sympathy-as-consumption?) pushed the work to privilege the physical over the linguistic, to emphasize sympathetic vibrations at the expense of ethical relations. Very little of the work is concerned with recognizing otherness, difference, or conditions of emergence. In real, lived interpersonal experiences, both the affective and the linguistic forms of relating become important, and slide into each other. One cannot encounter the other without some sensorial experience thereof, but once this encounter occurs, questions of ethics and politics must arise. What concerned me in this show was the extent to which sound’s especially strong capacity to articulate these questions of difference, history, and language was muted.7

Levinas’s theory of ethics moves pretty easily into the terrain of sound. He focused on the communicative power of the face in live interactions, eventually turning to a sonic metaphor to explain the exchange:

To give meaning to one’s presence is an event irreducible to evidence. It does not enter into intuition; it is a presence more direct than visible manifestation, and at the same time a remote presence – that of the other …. The eyes break through the mask – the language of the eyes, impossible to dissemble. The eye does not shine; it speaks.8

The eye speaks. The ethical, the demand to recognize another, operates according to sonic dynamics; more direct than the visible and at the same time remote. Doesn’t Levinas actually mean the voice? To say the voice speaks is not even metaphorical. The voice is the conveyor of language and meaning. That Enlightenment media theorist, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, wrote that “speech is the first social institution.”9 If this is so, then it is especially suspicious that there was no speech, or even vocalization, in this show. In an allegedly definitive, comprehensive, international survey of contemporary sound art, not a single voice was heard.

And if that absence wasn’t enough, Camille Norment’s piece put a fine point on it. Her sculpture, Triplight, is an old fashioned standing microphone cage in which the mic itself has been replaced by a flickering light, which casts uncanny shadows of the mic cage around the gallery. The shadows expand out on the walls surrounding the piece, and look more like a rib cage than like anything having to do with audio gear. The lack of the singing or speaking body is articulated in the shadows thrown against the walls of the gallery. The mechanism of receiving the voice is turned back outward, eschewing communication for objecthood, sound for vision. Norment points to the absence of the breath and voice in her piece, and perhaps to the way in which making something an fetish object rather than a communicative tool can foreclose liveness and humanity. I think this speaks to a larger gesture of the show in general. The voice is left out because it is so closely tied to meaning and speech, to the “social.”

Camille Norment, Triplight, 2008. Light sculpture. 1955 Shure microphone, light, electronic components. Dimensions variable. Exhibition view, MoMA, 2013. Photo: Jessica Feldman, 2013

Very few of the works, with a handful of exceptions, took responsibility for sound’s relationship to language and its ability to communicate meanings, feelings, and other lives. Seth Kim-Cohen expressed concerns, before the show even opened, that it was going to “rest on an imagined set of laurels granted to sound as the medium par excellence of the ineffable.”10 Ineffable means “unutterable,” unable to be articulated with language. Indeed, sound certainly has effects that are beyond words. But that is not all it is, or can be. For Barthes, sounding (“the injunction to listen”) has to be an act of intersubjectivity.

The injunction to listen is the total interpellation of one subject by another: it places above everything else the quasi-physical contact of these subjects (by voice and ear): it creates transference: “listen to me” means “touch me, know that I exist.”11

Put Barthes and Levinas together and it seems like you can’t have a show of soundings without having some ethical and political relationships rising up in the rooms. Yet the MoMA show seems largely to miss the opportunity. After the death of the author, we don’t know what to do, except to vibrate each other’s bodies with machines.

Hong-Kai Wang’s work is a strong exception to my complaints. Music While We Work lets us watch people listen, as I was inclined to do with Perich’s piece. In Wang’s piece, the conditions and agents of production are on the surface. Music While We Work takes form as a two-channel video and sound installation, which is really documentation of a more complex process. To make the work, Wang collaborated with Taiwanese political activist and composer Chen Bo-Wei and “a group of retired workers from a sugar refinery in the small industrial town of her childhood.”12 The workers and their families were asked to make audio recordings of the refinery that would “paint a world composed by their listening.”13 The videos document their recording processes from different camera views/perspectives.14 At the same time, we hear their recordings playing in the gallery space. There is a gap here: there is a slight distance between what the camera operator would hear and what the audio recording shows. Experiencing the piece, you feel multiple perspectives happening at the same time. The listener is implicated in this realization, as she is reminded of the difference between her situation as a museum visitor in NYC and the situation of the workers in the video. The audio in the installation is both noisy and referential, documenting the industrial sounds that these workers experienced daily for decades of their lives. What sounds like noise to the uninitiated likely has specific and nuanced meanings to those who have lived with these sounds on a regular basis for years. In listening and watching, the museum-goer recognizes that she is outside of the site. The layers of documentation point to the differences in perspective and understanding of the sounds.

Wang’s piece was my favorite of the bunch. The concept gave way to content that I felt I could learn from: I had the feeling that if I looked and listened harder and longer, someone else’s life and aesthetic experience of the world would open up to me a bit, even though my situation as an outsider was solidly accounted for. Yet, to do this, Wang needed to use video. There must be ways to do this with sound alone? If so, why did so few of the works in this show dare to approach topics of labor, otherness, and the maker’s and audience’s perspective? Instead of edging towards politics, participation, and relations, MoMA makes it look like sound got stuck once it got in the gallery. I wonder if the movement into the gallery space, particularly as it is folded into the commercial practice of buying and selling discrete art objects, is pushing sound art (or sound art curating) towards a type of product that denies the intersubjectivity inherent in the phenomenon of sounding.

I am not sure that the show’s predominant aesthetic is only a result of the architecture of the gallery space. It’s certainly logistically easier to put a bunch of paintings in a room than it is to put a bunch of soundings in a room. The more sculptures and drawings included in the show, the more pieces could fit in the space. So the push towards objecthood makes sense for this reason alone. However, an effort was made in this show to give the pieces some space to sound, to carve out mini-galleries, hallways, stairwells, and other interstitial spaces in which each sounding piece could live. The spacious nature of sound was acknowledged to a certain extent. Yet even those works that broke across the line of tape rarely addressed what it meant, politically or economically, to make a piece that wasn’t an object.

Pointedly in contrast, Allan Sekula’s Fish Story was hung just outside the Soundings show: a moving and gorgeous series of images about labor, the place of art in the workplace, shipping and commodities and commerce, war, poverty, the (unequal) distribution of resources, power and pollution. Why then, if such a work could indeed be housed in the museum, was Soundings so lacking in voices, politics, and critique? My thesis is that the combination of sound’s nature as a potent communicative tool and its tendency to not stay in its place, physically or metaphorically, was enough to push the people and their voices out of the sound art show. It’s one thing to make an image that addresses the question of the commodification of art, the relationship with the other, or political action. It’s quite another thing to make an artwork that, by the nature of the medium, can’t be easily owned, actually moves another’s body, and can speak literally, rather than symbolically. Such a work would be potent and dangerous, and wouldn’t work very well as an investment or piece of currency, because, both physically and thematically, it would resist commodification and would interpellate its owner.

The MoMA show made me worried about sound-as-art and its future in the gallery. The show seemed to presume that, in order to make sound into something that can live comfortably in a collection, language and politics have to be dumped out of it. In the effort to embrace the way sound is spatial and sculptural, or can be translated to a visual realm, the “plastic” and physical qualities of sound are isolated and depoliticized. The pieces that did move the body didn’t move the body to action. But they did cross that line that separates the art object from the viewer.

I think sound art can do more than this. It has the powerful possibility to break down the barriers between art and self because of the way sound works on the body, while also carrying messages and perspectives that originate somewhere other. There do exist spaces and curators who value this quality of sound.15 If sound art is going to break out of the “phenomenological cul-de-sac,”16 it needs the space to be about something more than its own psychophysics. It needs permission to take ownership for its operations on others as psychic and political subjects, not simply as resonating bodies, and to take on authorship, perspective, and voice. The next wave of artists, curators, and institution-builders will have to think critically and proactively about what kinds of physical and economic structures need to be in place in order for “soundings” to take on the fullness of their medium’s potential.

1 It’s worth noting that Perich is not the first one to make work in this vein. His piece bears striking resemblance Peter Ablinger’s white noise installations, Hans Koch’s Circle of Fifths, and Bernhard Leitner’s Wall Grid. Perich’s innovation in this tradition is that he made a tiny oscillator circuit for each pitch/speaker, allowing his 1500 channels to be held in one discrete wall hanging, without any patch cords. His work is less an installation and more a sculpture.

2 Video art, performance art, participatory art, relational aesthetics, etc. all have struggled with these questions and their role in the art institution for decades now. Tino Sehgal’s work is, perhaps, the example par excellence of artwork that succeeds at entering the marketplace and engaging the art institution without taking on material form. Sound art is a little late to the game, yet the questions still remain salient and unresolved. And sound, unlike performance, can be made more object-like. Unlike videos, sound art objects can be made un-reproduce-able and unique. Sound art sits at tricky nexus in the economy of artifacts.

3 Alvin Lucier’s much earlier work, The Queen of the South (1972), does almost exactly the same thing, but with sometimes-audible frequencies.

4 Wall text, Ridges on the Horizontal Plane, New York, NY, Museum of Modern Art, October 26, 2013.

5 Very briefly: Antonin Artaud’s “Body-without-Organs” is a concept deployed by Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari to describe a way of being in the world in which we are not conceived as discrete and stable entities bound by our skin, but as slow-moving and vibrating flows, who communicate with and activate each other through resonance. See section six of their text A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia (as translated by Brian Massumi, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1987).

6 Susan Philipsz, “Study for Strings,” dOCUMENTA (13), http://documenta.de/research/assets/Uploads/Studyforstrings.pdf.

7 Brandon W. Joseph, in his review of this show in Artforum, points to this quality in the discourse around sound and music. He writes, “ … sound art’s emotional impact is often understood to influence recipients without the intercession of social, historical, critical, or artistic knowledge. (This fantasy of unalloyed affectivity is itself a long-standing trope in the reception of music.)” Joseph doesn’t connect this directly to the art market, but he does connect it to problems of authority and expertise, “disciplinary anxieties” and the art world’s need to “shore up the independence of a category like sound art.” (See Brandon W. Joseph, “Soundings: A Contemporary Score,” Artforum, November, 2013, 282-283.)

8 Emmanuel Levinas, Totality and Infinity: An Essay on Exteriority (1961), trans. A. Lingis. (Pittsburgh, PA: Dusquesne University Press, 2007), 66. See also: http://www.iep.utm.edu/emp-symp/.

9 Jean-Jacques Rousseau, “Essay on the Origin of Languages in which Something is said about Melody and Musical Imitation,” in The First and Second Discourses together with the Replies to Critics and Essay on the Origin of Languages, ed. and trans. Victor Gourevitch (New York: Harper & Row, 1986), 240.

10 Seth Kim-Cohen, “Precepts – Concepts – Precepts,” Voice of Broken Neck, June 17, 2013, http://voiceofbrokenneck.blogspot.ca/2013/06/percepts-concepts-precepts.html.

11 Roland Barthes, “Listening,” in The Responsibility of Forms: Critical Essays on Music, Art, and Representation, Trans. Richard Howard. (New York: Farrar, Straus ad Giroux, 1985), 251.

12 Wall text, Music While We Work, New York, NY, Museum of Modern Art, October 26, 2013.

13 Wall text, Music While We Work.

14 Phill Niblock’s film series, The Movement of People Working, explores similar themes and imagery, but uses sound quite differently.

15 AVA (New York), Arika (Glasgow), Carsten Seiffarth (Berlin), Sonic Acts (Amsterdam), Michael Schumacher (New York), and SARC (Belfast) are perhaps some hints in the right direction.

16 Seth Kim-Cohen, In the Blink of an Ear: Toward a Non-Cochlear Sonic Art (New York and London: Continuum, 2009), xix.

Jessica Feldman is New York-based intermedia artist with a background in sound, sculpture, and installation. She moves among the worlds of new media art, electronic music, academia, and activism. Her works include sculptures, performances, interventions, installations, videos, and compositions. Many are site-specific, public, participatory, and/or interactive, and deal with the relationships among the body, technology, (the) media, and intimate psychological and communal social dynamics revealed by contemporary systems of control. Pieces have been performed, installed and exhibited internationally at art galleries, museums, concert halls, public parks, city streets, tiny closets, boats, the New York City subways, and the internet. New York venues include Socrates Sculpture Park, White Box, The Kitchen, LMAKProjects, Roulette, The Stone, and many outdoor locations. Her work has received awards from NYSCA, the LMCC, the Max Kade Foundation, Columbia University, Meet the Composer, and the Experimental Television Center, among others. She teaches sound art, physical computing, and interactive technologies in the Graduate Media Studies program at The New School and previously taught in the sculpture department at the Tyler School of Art at Temple University. She received an MFA in Intermedia Art from Bard (2007), an MA in Experimental Music from Wesleyan (2005), and a BA in Music from Columbia (2001) and currently is completing a PhD in the Department of Media, Culture, and Communication at NYU.

http://jessicafeldman.org/