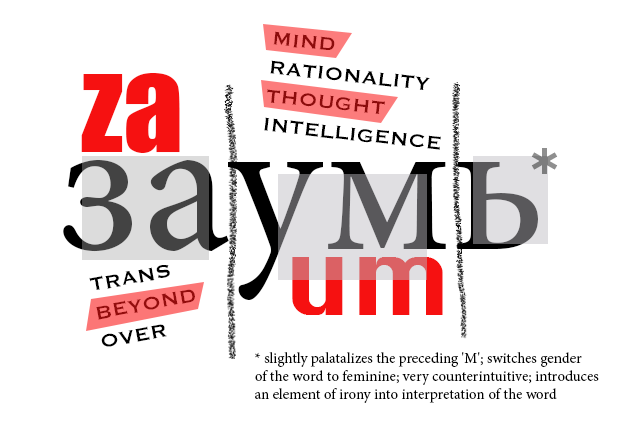

1. ZAUM’ was a form of invented language or a broad term for the particles of language floating above any clear meaning used in Russian “Futurist” poetry of the early twentieth century. This neologism formally appears in the writings of Aleksei Kruchenykh and Velimir Khlebnikov in 1913. The wordplay that defines the logic of this intentionally awkward combination of linguistic signifiers is: prefix “за” [trans, beyond, over], root “ум” [mind, rationality, thought, intelligence] and finally a soft sign “ь”. The last element in particular gives us a taste for the poets’ creative strategy by switching the gender of the word to feminine and bringing a hint of irony to the equation. To the Russian ear this is very counterintuitive, it is indeed highly disruptive and points to further acts of “linguistic terrorism” such as switched singular and plural markers, masculine/feminine/neutral gender manipulations and elaborate verb inventions.

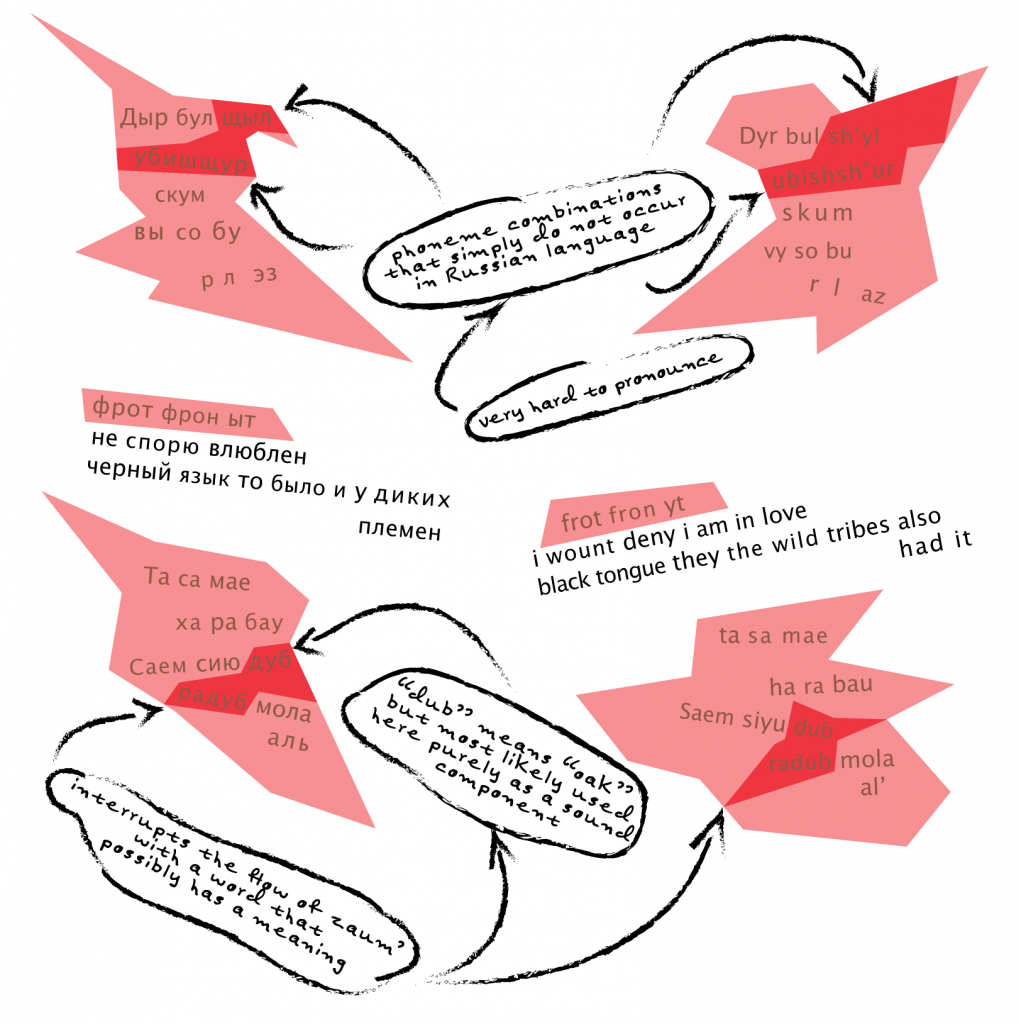

Unlike their Italian counterparts, who perhaps more comfortably wore the label of “Futurism”, Russian poets were not interested in onomatopoetic output; mimicry of the sounds of the industrial landscape of the early 20th century cities does not factor into their production. ZAUM’ is at its core a modernist undertaking, a language turned in upon itself. In their manifesto “The Word as Such” Kruchenyh and Khlebnikov state that there is more Russian character in the five lines of Khlebnikov’s “Dyr Bul Shchyl” then in all of Pushkin, the most celebrated poet within the Russian Literary tradition.

Scan of the original volume with Mikhail Larionov’s illustrations is available on the Getty Research Institute site.

Khlebnikov’s “Dyr Bul Shchyl” (Russian) Khlebnikov’s “Dyr Bul Shchyl” (English)2. Translation of ZAUM’ presents a very simple problem. To a person unfamiliar with Russian language ALL of the sounds are divorced from any grounding in the sphere of the semantic. It’s all ZAUM’! While I am using visual devices to try to convey the difference between “words” that loosely relate to standard Russian and purely phonetic inventions, I have to acknowledge an element of built-in failure in this project.

Yet it is precisely this failure that points to a greater production context within which the poets were operating, that of a multilingual Russian Empire. It was the last major autocratic power of Europe that had just completed a nearly two hundred year expansionist projects; one of the most ambitious and bloody in the history of humanity. It stood as the largest contiguous country in the world. Although its populations were forced to speak Russian, their native tongues ranged from Finish in the north to Georgian in the South, Polish in the West and Mongolian in the East. Russian native speakers of the early twentieth century encountered languages that were completely alien to them (literally hundreds of languages from a staggering variety of language groups) and in many cases this encounter forced them to reflect back upon the sound components of their own language.

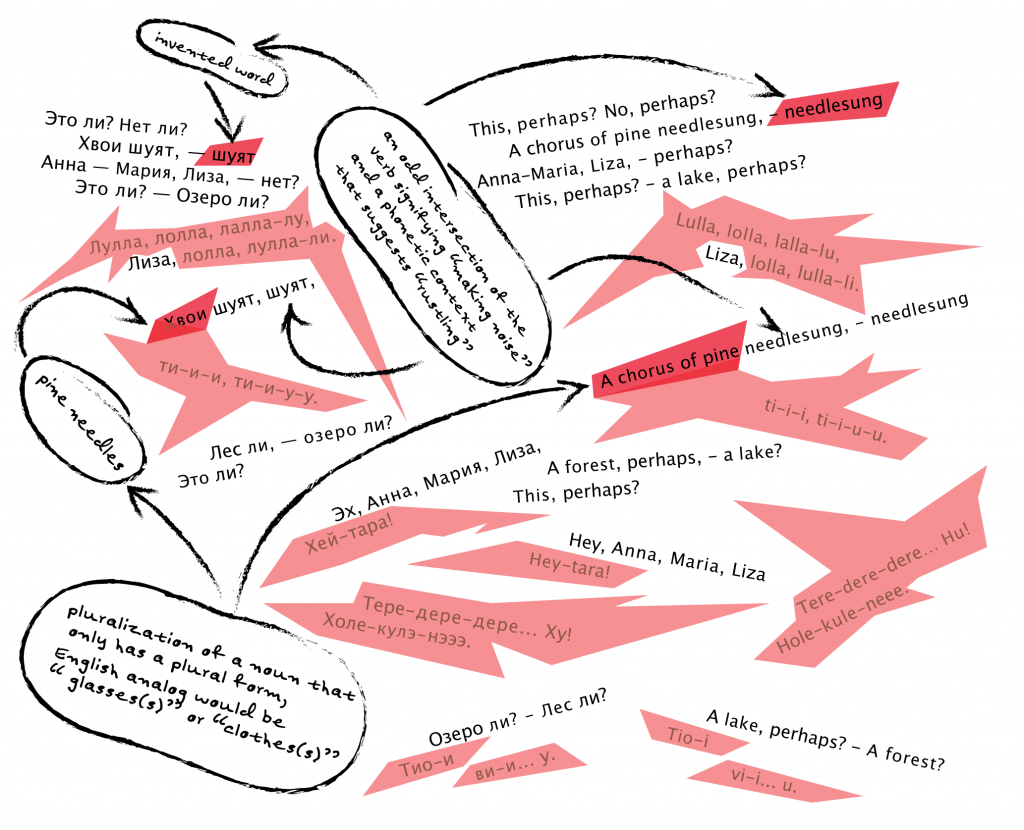

Guro’s “Finland” (Russian) Guro’s “Finland” (English)3. A clear case for cross-language influence on ZAUM’ is presented here in Elena Guro’s 1913 poem “Finland”. It appeared alongside the writings of both Kruchenyh and Khlebnikov in a volume entitled “The Three” which was produced by Guro’s husband (composer behind “Victory Over the Sun”) Mikhail Matyushin and illustrated by Kasimir Malevich. Unfortunately, 1913 was also the year of the poet’s death. This event resonated in a particularly painful way in the avant-garde circles, since Elena Guro was one of the organizing forces of the fledgeling experimental art and poetry scenes.

The poem, extremely interesting and innovative, is nevertheless also problematic in its Russocentrism. Guro, who was from a well-to-do family and had a summer house in the Finnish territories, was very sympathetic in her contact with the linguistic other. The work does however follow colonial patterns, underscoring and mirroring the unequal political power dynamics within the Empire. To the Russian ear, Finnish speakers’ tendency to raise the pitch of the end of sentences sounds much like a signifier of a question. Accented speech sounds like a never-ending set of questions presented in a series of sing-song patterns of double vowels and double consonants (another distinguishing feature of Finno-Ugric languages).

At this point it is important to state that I am bringing these issues up in order to give a reader a glimpse into the complex cultural mix of the region and not to belittle the importance of a poet who honestly has not gotten her due as of yet. In this context, Elena Guro’s mimicry of another language becomes a departure point for a very sophisticated sound exploration with a historical lineage all its own.

4. I was born on the 28th of October, 1885 at the encampment of the Mongolian Buddha-worshiping nomads.

(from Autobiographical Note [1914], Velimir Khlebnikov)

This is admittedly a rather fantastic beginning to one’s life that Khlebnikov’s ascribes to himself. In the Europe-facing capital of St. Petersburg (a much older Russian capital Moscow regains its status only after the Revolution) he is the exotic outsider from the wild frontier. Attempts at writing one’s own mythology aside, this statement is indeed based on real biographical facts. He was born in the area of southern Russian populated by Kalmyks, a nomadic group of western Mongolian people who are indeed Buddhist worshippers. Their language, Oirat (Mongolic group) is quite different from Russian (Slavic group), and together with the fact that from an early age the poet moved around with his family all over the South Central Russia, would have exposed him to an amazing number of linguistic constructions from a variety of cultures and languages.

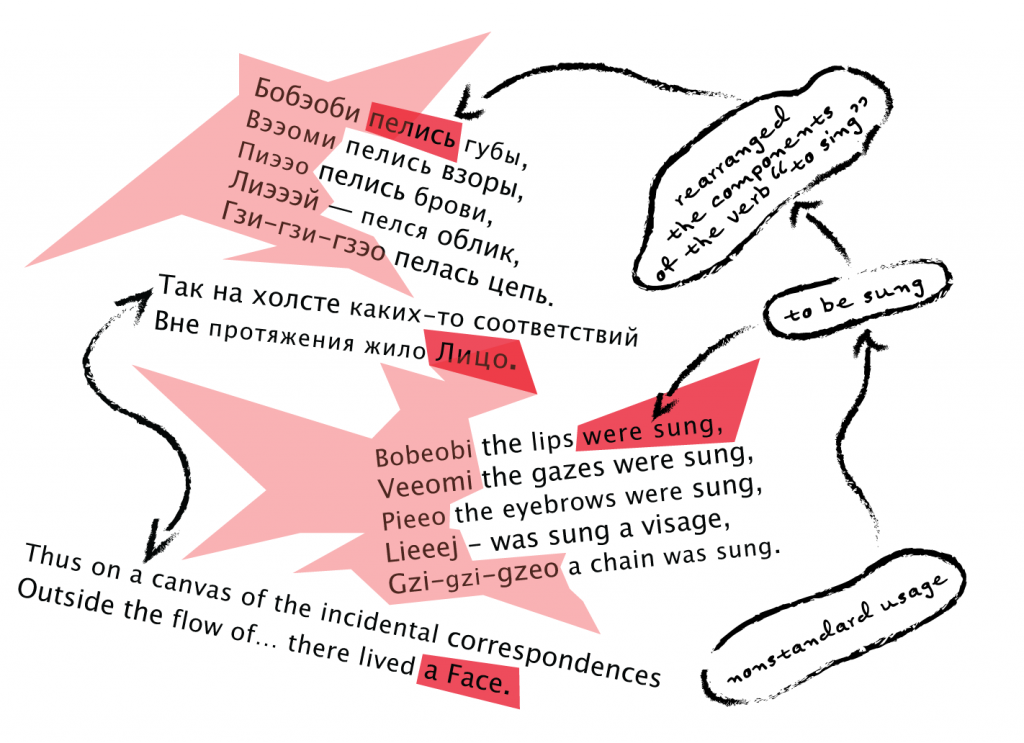

Khlebnikov’s “Bobeobe the Lips Were Sung” (Russian) Khlebnikov’s “Bobeobe the Lips Were Sung” (English)Khlebnikov’s poem “Bobeobe the Lips Were Sung” offers a rather early and highly experimental usage of sound elements of language. It was written in 1908, several years before the “official birth” of ZAUM’ but very much anticipates its development.

5. The three pieces that I chose to concentrate on are fairly well known works by, especially in the case of Khlebnikov and Kruchenyh, fairly well known authors. They have definitely been translated before (“Tango with Cows” at the Getty Museum and a related collection at PennSound are particularly interesting highlights). My translations and performance approaches are, in many instances, significantly different from what I found available in English. This speaks to both semantic polyphony that all translators have to wrestle with and my attempt to convey the dissonance of the sound/linguistic constructions as they present themselves in Russian.

I am not trying to resurrect lost pieces or justify yet another canon. My aim is to constructively problematize and give dimension to a project that very often becomes just a footnote in the history of the Avant-Garde.

6. Rebellion against the linguistic norms paralleled poets’ rebellion against the political oppression of the Russian Empire. Zaum’ was a natural extension of the discourse that rose up in opposition to oppressive tactics of the state. There is a temptation to view the poetic products of this group purely as innovations within a greater formal progression of Modernist narrative. This viewpoint however, robs the project of its radical political potential.

7. Writing about historical events is often complicated by the need to choose a scope for the project. In some ways Kruchenyh’s later contact with Georgian and Armenian experimental poets and Khlebnikov’s journeys to Persia can produce event more exciting cases for the conversation about inter-language exchange. At that point however, the Russian Empire was no more and the promise of a beautiful new day, mixed with the murderous acts of Red Terror, provided a very different backdrop.

8. Special thanks goes out to Marina Balina for invaluable advice on the translation and Gerald Janacek for being the most amazing guide to Zaum’ that anyone could wish for.

Dmitry “Dima” Strakovsky was born in St.Petersburg, Russia in 1976 and has lived in the United States since 1988. Dima completed his MFA degree at The School of the Art Institute of Chicago’s Department of Art and Technology and stayed in Chicago for several years producing art and working for various companies in the toy invention industry. Following his work in the commercial sector, Dima joined the faculty at the University of Kentucky and currently lives in reasonably urban parts of USA with occasional time off in reasonably rural parts of Japan. Dima’s practice spans diverse media and conceptual interests: collaborative performances, media installations, drawing and sculptural works are just some of the examples of different modalities that define his output.

Selected Sites and Projects:

http://www.shiftingplanes.org/

http://www.facebookportrait.com/

http://lprt.shiftingplanes.org/

https://vimeo.com/shiftingplanes