Author’s note: The installation discussed here was commissioned by the Museum der Moderne Salzburg in Spring 2016 as a part of the Group Exhibition “Art-Music-Dance” curated by Sabine Breitwieser, and then restaged at Murray Guy in Fall 2016.

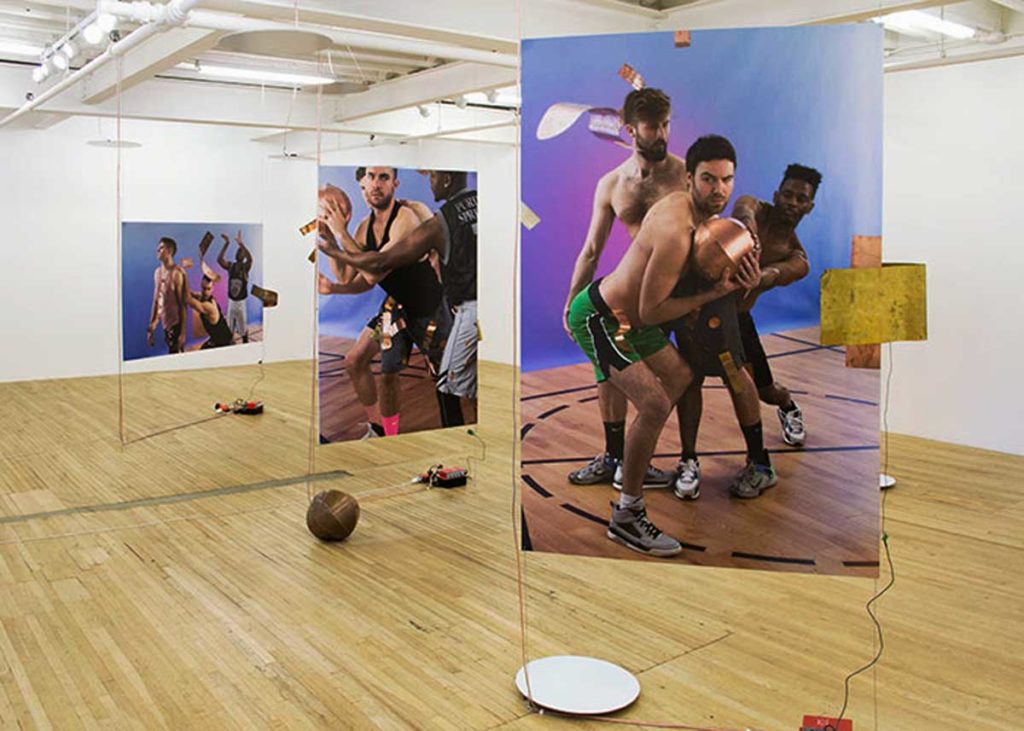

Over the past two years I have rekindled my love of basketball by playing in a gay basketball league. Games is an installation that bears the mark of that rekindled love. It consists of five double-sided life-size photo-sculptures. Each photo has a copper or brass “limb” attached that, when touched, triggers a stereo recording. Each photo contains 10-20 different recordings, ranging from 30 seconds to 4 minutes long. As the visitor walks through the installation, she is invited to touch these metal limbs to activate the sound, in whatever combination she wishes.

The models in the photos are dancers, actors and basketball players. They are partly re-enacting poses from Vaslav Nijinsky’s choreography for his ballet Jeux, as well as poses from NBA Instagram snapshots, and representations of basketball in television and advertising.

Composed in 1914 for the Ballets Russes, Nijinsky’s Jeux was set to music by Claude Debussy. It described a game of tennis between three dancers, whose games turned out to be less about tennis and more about the navigation of desire for one another. The dancers were played by two women and a man, but in his later diaries Nijinsky revealed that the ballet was supposed to depict three men. More specifically, it was meant to depict the homosexual relationship between Diaghilev, the impresario of the Ballets Russes, and two of his young male lovers, including Nijinsky himself. At the premiere, Nijinsky played the part of Diaghilev, while Tamara Karsavina and Ludmilla Schollar played the parts of Nijinsky and the other young lover of Diaghilev. The twisted and coded homosexual subtext of the ballet serves as a lens through which the installation of Games can be interpreted.

However, the installation is by no means meant as an attempt to re-create Jeux. Rather, the ghost of Nijinsky is resurrected through the sound itself in the continually changing combinations of physicalized sonic shapes and characters, as driven by the actions of the visitor. The visitor becomes an additional dancer whose agency as activator sparks a new dance between “sound characters,” sounding objects, and observers. All the while, the sculptural photographs act as markers, stationary queer bodies that insist on the context of this dance as gay basketball theater.

As to athletics and sound: Kathy Acker describes the mastery of the body via bodybuilding as learning “a language that is Speechless.” Through numerical and spatial repetition, “an aural labyrinth” of counting “reps,” a self may learn its own body’s language. Sound likewise operates on its own plane of understanding, as musical language is also without speech. This installation works similarly: through repetition of movements and actions, activating specific audio triggers at particular times, the visitor may learn the body of sound that constitutes the otherwise hidden crux of the show. The visitor may stay for just three minutes, touching only two different photo-triggers. Or she may stay thirty minutes, learning the ebb and flow of different recordings, re-activating triggers towards a deeper experience of the dancing body of sound that evolves over time.

The double-life of both Nijinsky and Diaghilev inserts a subtext of psycho-sexual drama into the ballet – an undercurrent of desire and repulsion. Read as such, the dancing bodies become queer bodies, shifting between languages – the language of movement, the language of desire, the language of music. Nijinsky’s legendary presence on stage was a seductive force that combined technical mastery with unique rhythm and an ability to connect to audiences. Here, sound takes on the role of creating stage presence. Sound not only animates the photographs, but acts as a seductive performer, luring the visitor to stay for more, while never fully giving up its entire being to the audience. The sound is an elusive performative force.

The two rooms of the installation consist of a front room – a public stage for the playful activation of a queer body of sound, and a back room – a private “locker room” for the private life of the performer or player. In the “double life” of Diaghilev, the basketball player becomes a kind of furniture queered by sound – reprogrammed to penetrate your body, to speak back. The triggered sounds function as intimate perceptual triggers, activating a sense of immediate presence, not unlike the performative presence of Nijinsky’s seductive arhythmic spirit1 and not unlike the experience of the basketball court stage, and yet, a presence more individualized, inducing intimate encounters.

1 It should be mentioned that Debussy was outspokenly against Nijinsky’s choreography. Though Nijinsky and Debussy collaborated on Prelude de l’Apres Midi d’un Faun, the music for which is fluid and graceful, the choreography for Jeux was mechanical and angular, drawing from Dalcroise Eurythmics, which takes a mathematical approach to rhythm and the body. Nijinsky reportedly said to the dancers, “Step through the beats of the music” in an attempt to get them to create their own arrhythmic counterpoint, not graceful in the conventional sense but reliant on the enigmatic stage presence of the performers and the dramatic sexual friction between them.

Sergei Tcherepnin is an artist operating at intersections of sound, sculpture, photography and theater. Attaching synthesizers, computers and amplifiers to small surface transducers—devices that convert electrical signals into vibrations—he orchestrates compositions in which objects are transformed into speakers. Often invoking queer, hybridized characters such as the “Listening Cactus,” the “Maize Mantis,” or the figure of the Pied Piper, Tcherepnin’s scenarios cultivate play between things and bodies, compelling the audience to develop a “score” for handling these animated objects. These interactions suggest new possibilities for intimacy with sound, where “listening” involves a more expansive state of activity: listening by touching, listening by opening, listening by feeling, listening by harnessing, or listening by walking.

He has staged solo exhibitions at the MIT List Visual Arts Center, Audio Visual Arts, Halle fur Kunst Luneburg, Murray Guy Gallery, Karma International and Overduin & Co, and has held performances and participated in group exhibitions at Museum of Modern Art, Guggenheim Museum, Yvon Lambert, Pace London, SF MoMA, Pavilion of Georgia at the 55th Venice Biennale, Museum der Moderne Salzburg, 30th São Paulo Biennial, Greater New York at MoMA PS1 and 2014 Whitney Biennial.